Who Was Jesus... A Prophet of Woe?

Article # 1: An Introduction to Understanding the Historical Jesus

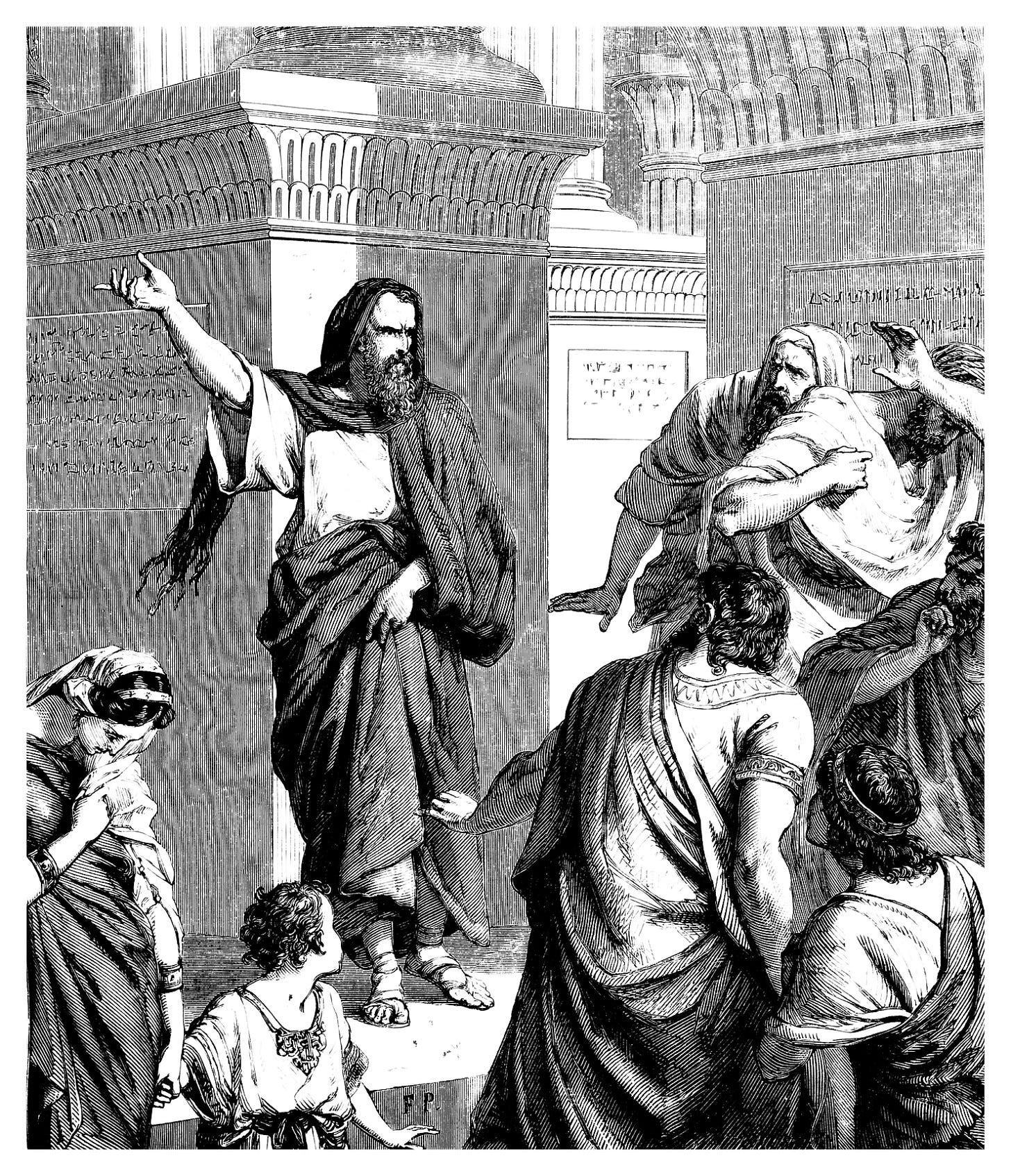

“Woe to Jerusalem”

Jesus cried out, “A voice from the east, a voice from the west, a voice from the four winds, a voice against Jerusalem and the sanctuary, a voice against the bridegroom and the bride, a voice against all the people…Woe to Jerusalem”1

These are the words of the prophet Jesus; but not Jesus of Nazareth.

The Jewish Historian Josephus records this oracle on the lips of Jesus, the son of Ananias. Josephus tells us Jesus ben Ananias began proclaiming the impending judgment of Jerusalem four years before the outbreak of the Roman-Jewish War in 66CE. Some of the leaders did not take kindly to Jesus’ woeful message, so they had him arrested and brought him before the Roman governor, Albinus.

While being brutally reprimanded by the governor, Jesus did not cease his lament over the city but persisted – between lashes – to cry out all the more, “Woe to Jerusalem!” When asked who he was and what he was doing, he replied only, “Woe to Jerusalem.” In light of this seemingly bizarre behavior, the governor deemed Jesus to be out of his mind and released him. According to Josephus, even to the very last moments of his life Jesus did not cease his prophetic warning.

Josephus says,

“so for seven years and five months he continued his wail, his voice never flagging nor his strength exhausted, until in the siege, having seen his presage verified, he found his rest. For, while going his round and shouting in piercing tones from the wall, ‘Woe once more to the city and to the people and to the temple,’ as he added a last word, ‘and woe to me also,’ a stone hurled from the ballista struck and killed him on the spot. So with those ominous words still upon his lips he passed away”2

Had he lived to see the outcome of the Roman-Jewish war, Jesus ben Ananias would have seen his words vindicated, as the city lay in ruins and the once glorious temple was burnt to the ground. So goes the story of Jesus ben Ananias who believed himself to be Jerusalem’s final prophet.

But what does Jesus the son of Ananias have to do with Jesus the son of Joseph?

Before answering, consider the following words from Jesus of Nazareth as he looks upon Jerusalem in tears:

“Would that you, even you, had known on this day the things that make for peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes. For the days will come upon you, when your enemies will set up a barricade around you and surround you and hem you in on every side and tear you down to the ground, you and your children within you. And they will not leave one stone upon another in you, because you did not know the time of your visitation” (Luke 19:42-44).

These words from Jesus of Nazareth sound remarkably similar to those of Jesus ben Ananias. But did Jesus really warn of a coming judgment against Jerusalem and the temple, and if he did, what would that mean for our understanding of him?

Understanding What Jesus Meant

In the remainder of this article - and the series of articles of which this is the first - I want to put forward a seemingly paradoxical thesis which I hope to develop.

The thesis is that we need to first understand what Jesus meant in his own time before we can begin to understand what Jesus means for our own time. Or, to put the point more sharply, we understand what Jesus means by understanding what Jesus meant. But this leads immediately to a question: what is the role of history in understanding Jesus?

The thesis is that we need to first understand what Jesus meant in his own time before we can begin to understand what Jesus means for our own time.

C.S. Lewis or G.B. Caird?

In order to answer this question, we will engage briefly with the views of two beloved Christian scholars of the 20th century, G.B. Caird and C.S. Lewis. George Caird was a New Testament Scholar at Oxford, one who in no small way contributed to the study of Jesus in his historical context. C.S. Lewis, also a professor at Oxford and then Cambridge, taught Medieval Literature and was an extremely influential lay Christian writer. Although the two had a good deal in common, they had markedly different opinions on the role history should play in the study of Jesus.

C.S. Lewis

Let us begin with C.S. Lewis. In his well-known Screwtape Letters, Lewis has the Senior Devil Wormwood tell his nephew named Screwtape that he ought to try to get his “patient” – that is the person he is tempting – to take up interest in the historical Jesus. Lewis provides several reasons for thinking historical Jesus research is contrary to the Christian faith, such as that it directs people’s devotion to something which does not exist and places the importance of Jesus on a message he taught rather than on who is and what he did, thereby destroying the devotional life. Not to mention that very few people become Christians through reading a biography of Jesus, and a full biography cannot in fact be written given the limitation of sources.

As always, Lewis expresses his point cleverly and clearly, but should we agree with him? Being a fan of Lewis, it may be tempting to say yes, but perhaps the best compliment we can pay a great thinker is to take them seriously enough to argue with them. And so we shall.

Lewis was well aware of the need for history in illuminating our understanding of past people and their thoughts, and the work he did in his field demonstrates that quite clearly (his books The Discarded Image, for example). So why did he think that history, which was so important in his own studies of medieval literature, should not be applied to help us understand Jesus?

I will not attempt a full answer here, suffice it to say that the general trend of historical Jesus research led many to the same conclusion, but the direction of Jesus research was about to change owing significantly to George Caird.

G.B. Caird

Caird believed that we, as Christians, not only can learn a great deal about Jesus from history, but that we must. Caird said,

“Anyone who believes that in the life and teaching of Christ God has given a unique revelation of his character and purpose is committed by this belief, whether he likes it or not, whether he admits it or not, to the quest of the historical Jesus. Without the Jesus of history the Christ of faith is merely a docetic figure, a figment of pious imagination. The Christian religion claims to be founded on historic fact, on events which happened [under Pontius Pilate]; and having appealed to history, by history it must be justified”3

If, then, we as Christians are in some sense committed to the quest of the historical Jesus as Caird believed we were, what does this mean?

Does it mean - as many have been led to believe - that methodological skepticism must be masked as history, granting only a few fragmentary sayings and leaving us with an unintelligible shadow from the past rather than the lively, challenging figure we confront in the Gospels?

The short answer is no.

What, then, does studying Jesus in his historical context mean? I think it means this: that we must make use of the best critical history available - not to replace or supplant the Gospels - but in order to attempt to understand the Gospels as they are preserved for us in the belief that through doing so we can better come to understand the Jesus in whom God has uniquely made himself known.

Jesus: Jerusalem’s Final Prophet

Since I have argued that we must understand what Jesus meant in order to understand what Jesus means, where are we to begin? We could simply jump in by selecting a saying from the Gospels and trying to make sense of it. In that case, say we stumble upon Luke 13:34-35:

“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! Behold, your house is forsaken. And I tell you, you will not see me until you say, ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!’”

In this passage, Jesus is warning that God is going to judge Jerusalem if the people do not turn back from their current path. But, what was their current path and why would Jesus be interested in a political matter like the destruction of Jerusalem?

When Jesus says, “your house is forsaken,” is he referring to their individual homes, or could he have meant that the temple - which was referred to as the house of God (see 2 Samuel 7) - was also going to be destroyed?

But again, why would Jesus be concerned whether the temple stood or not?

Also in this passage, Jesus speaks on behalf of Israel’s God, as did many of the former prophets in the Hebrew Scriptures. What is his connection with these earlier prophets?

Finally, Jesus says that God intends to shelter his people from the coming judgment, like a hen protects her children under her wing, but they’re not willing. Is Jesus then saying, in other words, that his own mission and message are aimed at diverting the disaster which he sees coming upon the nation?

Does Jesus see himself as Jerusalem’ final prophet? And if so, how would that relate to his being the savior of the world and the Son of God?

These are some of the questions that arise when we attempt to seriously answer the question, what did Jesus mean to his contemporaries and so what does he mean to us.

What is the way forward?

I hope to show that the way forward is to situate Jesus with his context in the first century and within the unfolding biblical narrative. With this in mind, the next article in this series will begin “in the beginning”…

Book 6, Chapter 5, Section 3, Flavius Josephus, The Wars of the Jews.

Book 6, Chapter 5, Section 3, Flavius Josephus’ The Wars of the Jews.

Jesus and the Jewish Nation, G. B. Caird.